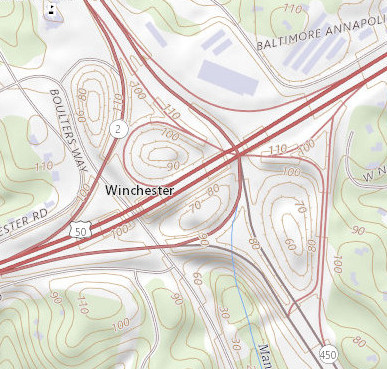

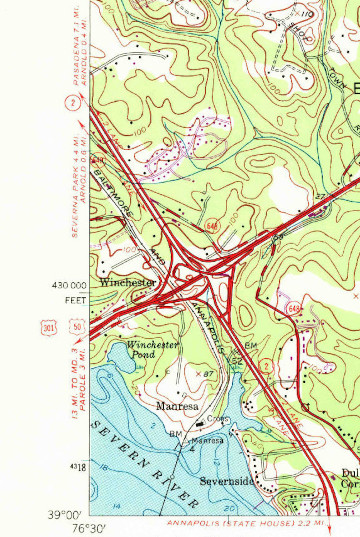

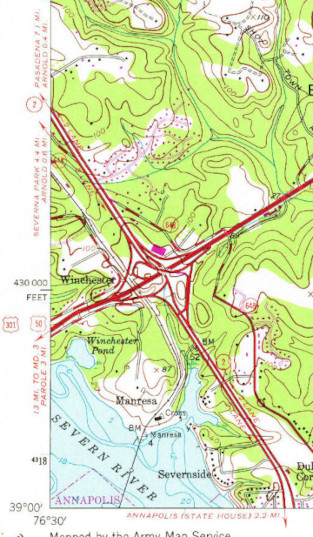

The map above shows the interchange between US-50/301 (Revell Highway/John Hanson Highway) and MD-2/MD-450 (Ritchie Highway). Source: US Geological Survey.

I've had an interest in transportation for a very long time. Thanks to websites like Steve Alpert's Alps Roads and Steve Anderson's Eastern Roads collection, I've gathered an appreciation for the history of highways. During my time in Delaware, I've had the opportunity to work with planners in various capacities, including serving on Newark's bicycle committee and the Dover/Kent County Metropolitan Planning Organization's public advisory committee.

I've also started performing my own independent research on highway histories. My first major project is presented here, which is my review of the Annapolis Bypass, carrying US-50, US-301, MD-2, and (unsigned) I-595 just above Maryland's state capital. My initial point of interest wasn't the bypass itself, though. I was mainly interested in answering one question.

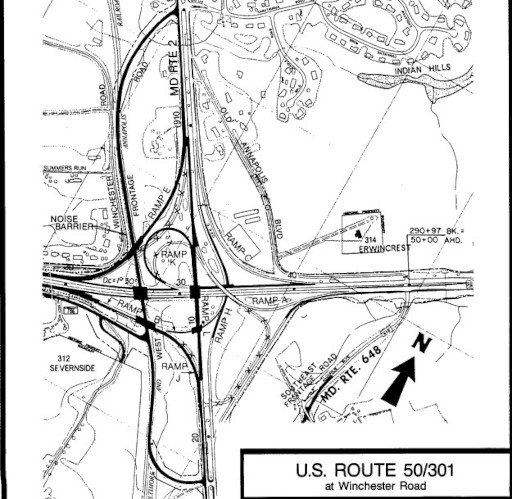

Why is this interchange SO WEIRD? It may not look so interesting at first, until studying the southbound movement. As described below, despite this appearing to be an interchange which directly serves all movements, it lacks a direct connection between MD-450 NB and US-50 WB/US-301 SB/MD-2 SB and, more importantly, requires the former southbound "through" movement (MD-2 SB to MD-450 SB) to navigate through some peculiar movements and come to a stop sign, facing the former northbound "through" movement (MD-450 NB to MD-2 NB). Alas, I was very interested in determining what led to this interchange's strange design.

In the 1940s, Maryland was proud of their newly completed link between Baltimore and Annapolis, the Ritchie Highway. This provided a four lane divided highway between the state's largest city and its capital.

Prior to the construction of the Bay Bridge and the modern US-50/US-301/MD-2 Severn River Bridge, the entrance into Annapolis was straightforward, literally. Traffic continued down the four lane Ritchie Highway until it reached the Severn River Bridge by the US Naval Academy. This was a two lane draw bridge, which would be a major bottleneck as it entered the city.

Then as the 1940s continued, higher speed roads were being planned throughout the country and certainly in Maryland. One plan was the Washington-Annapolis Expressway, today's I-595/US-50/John Hanson Highway. This also involved a connection to the Chesapeake Bay Bridge (yet to be built) and the eventual increases in traffic that would bring (there was a road built that linked to the ferry service that acted as a stop gap in its place until its completion). Between these was the Annapolis Bypass. With the Annapolis Bypass came a new crossing of the Severn River, which would carry multiple lanes of traffic. The Annapolis Bypass and eventual connector to the Bay Bridge are known as the Revell Highway.

Prior to the construction of the Annapolis Bypass, the connector route to the Bay Bridge (and Bay Ferry, at the time) simply met the Ritchie Highway at a T intersection. The map to the below shows the configuration of the intersection prior to the construction of the Annapolis Bypass. There's nothing too significant to note with this interchange.

Then came the Annapolis Bypass and a new four way interchange with the Ritchie Highway, to the east of the new Severn River Bridge. This new interchange was quite odd and remains as such today. A map of the interchange was shown towards the top of this page. What's really odd about this configuration really becomes apparent when looking at the southbound movement along Ritchie Highway. Note that southbound to southbound traffic (arguably the original "through" movement for MD-2) must meander through an odd set of ramps, then must come to a stop sign and make a left turn to continue southbound into Annapolis. More odd is that the northbound to northbound movement along Ritchie Highway essentially continues straight through the interchange. In fact, southbound to southbound traffic must cross northbound "through" traffic at the stop sign!

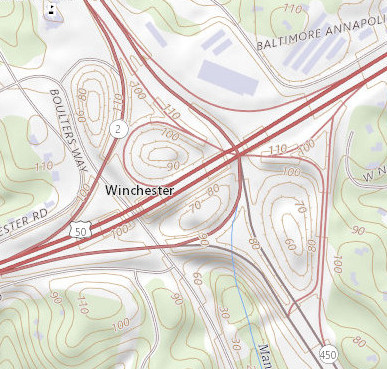

I have tried reviewing multiple sources to understand why this

interchange is designed so weirdly. This has involved contacting

the Maryland Department of Transportation (MDOT), where one of

their employees helpfully sent me environmental impact statements

for the corridor from the 1980s. It has involved extensively

researching Maryland's Public Archives and their online scans of

documents. It has involved reviewing aerial images from the US

Geological Survey. I found a traffic study from 1950 on Annapolis

travel patterns. I found MDOT highway maps from 1950 to 1954,

which documented the evolution of the proposed route of the

Annapolis Bypass.

Diversion: The maps above show the evolution of the Annapolis

Bypass from 1950 to 1953. Initially, the

Annapolis-Washington Expressway was to enter Downtown Annapolis

from the west, with the Revell Highway acting as a separate

highway, splitting from the Annapolis-Washington Expressway and

heading north. In 1951, this changed to the expressway

continuing directly east-northeast, as it does now, with a spur

route into Annapolis, but starting west of the wider portion of

Weens Creek. In 1952, the spur into Annapolis was

straightened and entered the city further to the east. I

believe this eventually became Rowe Boulevard, MDOT's preferred

route for traffic into Downtown Annapolis. Map Source: Maryland

Department of Transportation, via Johns Hopkins University.

Yet, after many hours of research and document analysis, I don't have a good answer as to why this interchange has such a weird design. That said, after reviewing all these maps, plans, studies, and other documents, I have come up with a few theories. Associated images will be shown, as well.

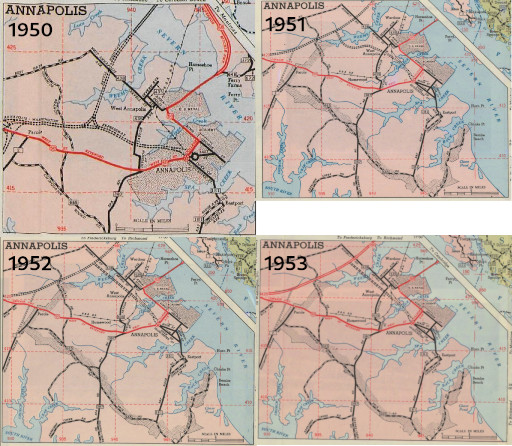

The image above shows the two-lane Severn River Drawbridge

entering Downtown Annapolis, as of August 1959. During

this time, the US-50/US-301/MD-2 Severn River Bridge carried 4

lanes of traffic. Today, it carries 7 lanes of

traffic. Source: US Geological Survey, Earth Explorer,

1959.

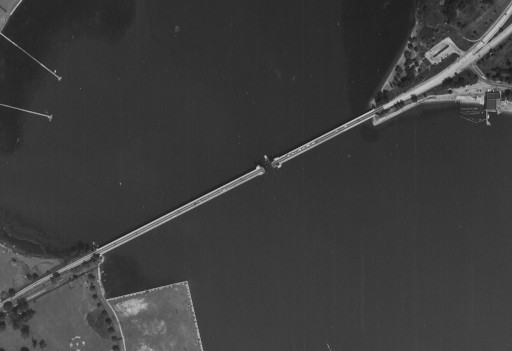

The maps above show the eventual abandonment of the Baltimore

and Annapolis Railroad. The map on the left is from

1971, the map on the right is from 1979. Source: US

Geological Survey, Topo View.

The drawing above shows proposed improvements from around

1986, particularly focusing on the interchange in

question. Improvements like this were also found in the

Baltimore-Annapolis Transportation Study from the early 1980s,

when many alternatives for today's Interstate 97 were

proposed, either following the MD-2 corridor or the

(ultimately selected) MD-3 corridor. Source: Maryland

Department of Transportation, via Maryland State Archives.

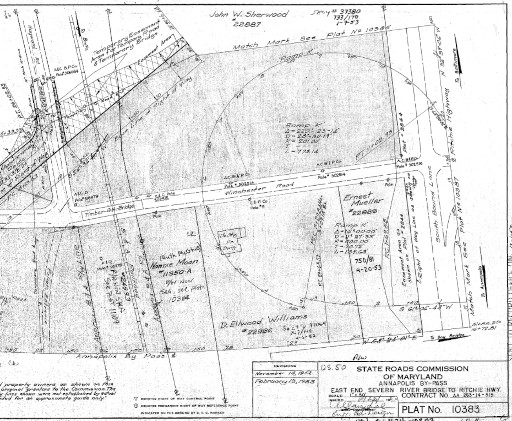

Some further research may indicate that the proximity of the Baltimore and Annapolis Railroad could have impacted the design of this interchange. This involved reviewing right-of-way plat data from MDOT, particularly those associated with projects AA-263-014-515 (Annapolis Bypass, Severn River Bridge to Ritchie Highway) and AA-263-022-515 (Ritchie-Revell Interchange).

Right of Way Plat 10383, showing the northwest quadrant of

the Ritchie-Revell interchange, as of 1952. Source:

PLATS.NET, Maryland State Archives.

The above image shows the most interesting right-of-way plat involved in the construction of this section of the Annapolis Bypass, when studying the design of the Ritchie-Revell interchange's odd design. It focuses on the northwest quadrant of the interchange, showing the proposed path of the ramp connecting southbound Ritchie Highway traffic to the Severn River Bridge on the Annapolis Bypass, as well as the loop ramp connecting westbound US-50 traffic to southbound Ritchie Highway.

The location of the loop ramp is extremely important in understanding what could have led to the bizarre southbound-southbound "through" movement for Ritchie Highway traffic, and it has to do with the right-of-way for the Baltimore and Annapolis Railroad.

This finding certainly gives more weight to Theory #3, that the Baltimore and Annapolis Railroad's location impacted the interchange design. This is not too surprising, as private railroads were effectively still in competition with state transportation agencies in the 1950s. A more extreme example is the Schuylkill Expressway's route near 30th Street Station in Center City Philadelphia. Apparently, because the Pennsylvania Railroad did not want to give any land for the construction of the highway, PennDOT had to build the highway right up against the Schuylkill River, tunneling under the streets abutting 30th Street Station, one of the busiest railroad stations in the country.

All that being said, I'm not discounting my other theories, that

the Navy likely wanted to divert so much traffic from approaching

the Naval Academy unnecessarily and that MDOT wanted to divert so

much traffic from approaching Downtown Annapolis unnecessarily,

especially if the crossing of the Severn River near the Naval

Academy was going to remain a two-lane roadway.

Links were active as of publication of this article on December 30, 2023.