The New Castle-Pennsville Ferry in 1936. Source: Delaware Public Archives.

This article discusses historical proposals for a fixed crossing over the Delaware Bay, ranging from studies performed in the 1960s to modern discussions over the feasibility of such a crossing. There are several sections, listed below:

On August 15, 1951, a major link in the road network of the northeastern United States was formed. The four-lane Delaware Memorial Bridge opened, replacing ferry service across the Delaware River, from New Castle, Delaware to Pennsville, New Jersey.

The bridge initially just carried US Route 40, running west to Baltimore and east to Atlantic City. On the western shore, this bridge also reached US-13, the main north-south route across Delaware and US-301, the main route from Wilmington to the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Washington. On the eastern shore, it also reached US-130, which eventually meets US-1 to reach New York City.

On the eastern shore of the Delaware River, in 1952, the New Jersey Turnpike was completed, with its southern terminus at the Delaware Memorial Bridge and its northern terminus just shy of the George Washington Bridge to New York City. Today, this is one of the busiest highways in the United States, serving as the backbone of the Northeast Corridor. On the western shore, in 1963, the Delaware Turnpike opened, providing a faster route from the Delaware Memorial Bridge to Baltimore and Washington. Today, the bridge officially carries both Interstate 295 and US Route 40.

This bridge was particularly significant, because it was the first bridge constructed over the Delaware River south of Philadelphia. This meant that traffic from New Jersey, New York, and New England could more easily travel to Delaware, Maryland, and points south (and vice versa), while bypassing the second largest city in the eastern United States. As a result, the bridge became extremely popular and well-traveled.

Some might even say the bridge was too popular. Less than 10 years later, officials from Delaware and New Jersey were discussing how to supplement the Delaware Memorial Bridge. In 1968, the second span of the bridge opened, making it the “twin span” bridge that it is today.

In 2019, the bridge saw an average of 100,210 vehicles per day (50,105 southbound toll transactions), according to an October 2021 press release from the Delaware River and Bay Authority (DRBA). This is similar to traffic counts on Interstate 95 south of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in Center City Philadelphia (50,980 northbound, 55,056 southbound).

The bridge's popularity leads to some oddities in terms of signage and roadway configuration. There are signs along US Route 13 in Camden, Delaware, about 50 miles south of the bridge (and I-95), which mention it as the route to I-95. As traffic approaches the bridge, there are several mentions that the bridge is the route to New Jersey and New York.

Since this bridge serves such a large number of travelers, it carries considerable traffic onto its approach roads. The section of I-95 just south of the I-295 interchange is easily the busiest segment of road in Delaware, seeing an average of 219,865 vehicles per day. Just north of I-295, this drops all the way to 95,743. This suggests that, on average, about 56% of traffic on I-95 in Delaware is likely using the bridge!

This section of I-95 is very busy and suffers from congestion, particularly in the lanes that exit to I-295. Over the years, there have been considerations for further supplementing the bridge, though with a new crossing further south along the Delaware Bay.

There is only one other bridge crossing the Delaware River south of Philadelphia, which opened in 1974. That is the Commodore Barry Bridge, connecting Chester, Pennsylvania and Bridgeport, New Jersey. This is a truss bridge with five lanes, carrying US Route 322. On its eastern shore, the Commodore Barry Bridge effectively just connects to a two-lane rural highway. This road does connect to I-295 and the New Jersey Turnpike, but again, it's only two lanes. On its western shore, the bridge connects to a chronically congested stretch of I-95. Thus, it really supplements traffic needs on both sides of the river, rather than relieving the Delaware Memorial Bridge.

About 70 miles south of the Delaware Memorial Bridge, a ferry service operated by the Delaware River and Bay Authority, the Cape May-Lewes Ferry, provides a link between coastal areas in Delaware and New Jersey. This service is very seasonal in its nature, with more frequent and more expensive service in the summer months.

Naturally, with the crossing of a large body of water, the question of a bridge has come up many times. These discussions date back as far as 1962, when the second span of the Delaware Memorial Bridge was being discussed.

In the July 25, 1962 hearings before the Congressional Subcommittee on Rivers and Harbors, this statement was made by Representative Milton W. Glenn from New Jersey (emphasis added, page 27):

"Of course, the main purpose of this legislation is to enable the newly created Delaware River and Bay Authority to build another toll bridge across the Delaware River, adjoining the present Delaware Memorial Bridge. The traffic on the present bridge is so heavy that it is estimated that within the next 2 years, it will not be able to serve the heavy traffic, which is increasing every year. The authorization of the new bridge will, of course, alleviate this condition, but is [sic] cannot come too soon. With the march of time, it is highly possible that another crossing, either bridge or tunnel, may be necessary between the two States at a point farther down the river and bay, and perhaps halfway between the present structure and the 70-mile-distant location for the ferry service to which I have heretofore referred."

There was support on the other side of the river, as well. In the 1983 book, Crossing the Delaware: The Story of the Delaware Memorial Bridge, by William J. Miller, Jr., then-Executive Director of the DRBA, stated that a Delaware state senator also expressed support for a bridge further down the Delaware (page 67):

"There was little if any opposition to the new bridge project. When the Corps of Engineers solicited public comment on the project, the only known reply came from a Delaware state senator who had served on the committee which helped create the Authority. The senator suggested consideration be given to putting the bridge further downstream. His suggestion, however, received minimal attention or support."

Some official planning documents went as far as suggesting that a bridge, or even bridge-tunnel, was on its way. These documents were extremely difficult to find and were often found when researching other, seemingly unrelated transportation projects.

The 1965 report, The Impact of Population and Economic Growth on the Environment of New Jersey, from the New Jersey Department of Conservation and Economic Development stated (emphasis added, page 112):

"Cumberland County is one of the State's major agricultural counties, specializing in vegetable, egg, and poultry production. It is also the location of manufacturing activities requiring the local resources of glass sand, clay, and gravel. The rate of growth of the County has been moderate as a result of the County's distance from the major urban centers in and around the State. The entire southern boundary of the County, fronting on the Delaware Bay, consists of marshes and wetlands, which have acted as a natural barrier to waterfront development. Thus, Cumberland has neither port facilities nor the resort facilities of neighboring Cape May County. The oyster industry, once a major employer in certain areas of the County, has experienced a sharp decline due to a parasitic disease which seriously depleted the oyster stock. A proposal for a bridge-tunnel complex to connect Cumberland County with Delaware and points south could prove of great benefit to the future development of the County. Present trends, however, indicate only limited growth for the County in the near future."

The New Jersey Department of Transportation (NJDOT), who should have significant interest in a project like this, only seems to have considered the Delaware Bay Bridge in a very small timeframe. The state's 1963 and 1972 master transportation plans do nothing to suggest that a Delaware Bay Bridge was even under consideration.

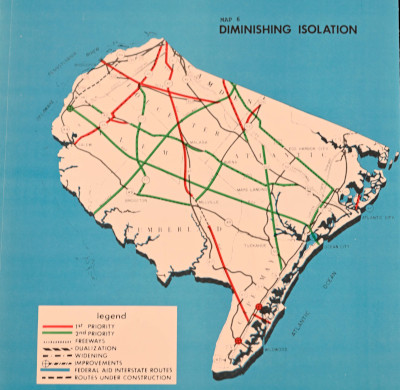

However, the 1968 New Jersey Transportation Plan incorporates a highway called the "Midstate Thruway," which was to have run approximately to the east of the mouth of Stow Creek (at the Salem/Cumberland County line) and continue north-northeast all the way to the now-cancelled NJ-38 freeway, west of Fort Dix. I've traced the statewide plans using QGIS. For this map, I assumed that Delaware Route 6 would continue into New Jersey as New Jersey Route 6, as NJ-6 has been unassigned since 1953.

There is no suggestion of a pathway for the bridge, though it sits about 5 miles northeast of the eastern terminus of DE-6 at Woodland Beach. It could be assumed that this bridge would extend DE-6 into New Jersey on an approximately straight path.

Without even considering the bridge, this highway would have been about 60 miles long! Even still, NJDOT marked the Midstate Thruway as a "2nd Priority" and had nothing written about the highway anywhere in the document. I couldn't find any mention of the highway in any other New Jersey transportation documents. However, the 1980 study on the Delaware Bay Bridge also seemed to mention this highway, though it described a very different northern terminus.

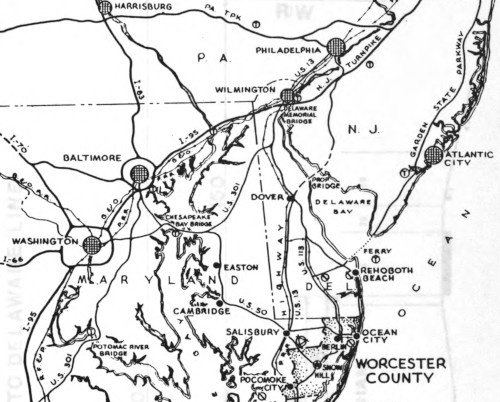

This is what I meant by "seemingly unrelated transportation projects." In the 1972 environmental impact statement for US-113 improvements between Berlin, Maryland and the Delaware state line, there is a map titled Location of Worcester County, Maryland prepared by the Worcester County Planning and Zoning Commission. Presumably, this map dates to the late 1960s or early 1970s.

On this map, there is a "Proposed Bridge" running from Dover, Delaware into New Jersey, continuing along what is, presumably, an extension of the Ocean Highway designation.

Tracing the map using QGIS, I am assuming the route for the bridge and extended Ocean Highway described below.

This study provides a synopsis of the 1963 and 1970 studies prepared for the DRBA, concerning a Delaware Bay Bridge connecting Woodland Beach to Sea Breeze. The study ultimately concludes that there was likely not enough of an economic benefit, both to the region and to the DRBA, to justify the expense of building such a crossing.

While the aforementioned studies mainly focused on the Woodland Beach to Sea Breeze route, this study also detailed a potential crossing to replace the Cape May-Lewes Ferry. While both routes are discussed, the same conclusion is drawn for both, though for different reasons. In lieu of quoting the entire rationale, this can be found in pages V-2 to V-6 of the study.

Even still, this study included a potential engineering design and location for a bridge, specifically one that would run between Lewes and Cape May. I attempted to mark this on a map using QGIS, which can be found in the map at the end of the next section. The basic engineering design proposal is copied below (page V-6):

"One alignment would be to have bridgeheads at Cape May Point at the north end and in the vicinity of the western boundary of Cape Henlopen State Park at the southerly terminus. The north approach would have an alignment curving to the west and north of the built-up portions of Cape May itself and would connect to the south end of the Garden State Parkway. The south approach would extend from the bridgehead to U.S. Route 9 and State Route 14 [today's Delaware Route 1].

The horizontal alignment of the bridge structure would have a southwesterly bearing from Cape May Point over the Cape May Channel to the area of Middle Shoal. It would then curve to a more southerly bearing in the area of the Overfalls Shoal to take advantage of the lesser water depths there and then bear southwesterly again over the Pilot Area. This alignment would then cross the Cape Henlopen spit about a half mile south of its point and extend over the easternmost portion of Lewes Harbor to the landfall or bridgehead location.

The vertical alignment would include a clearance of about 175 feet over the main deep-draft navigation channels near the Pilot Area as well as a high level crossing of the Cape May Channel. Over the shoals low-level trestle connection with clearances of the order of twenty-five feet may be practical. Transition sections at an appropriate highway grade would be utilized between high- and low-level bridge sections.

The low-level trestle could consist of 100-foot span lengths using repetitive design and construction methods. Transition and high-level spans other than main spans could be of girder or truss design with spans in the 300-foot to 500-foot range. The main span over the deep-draft waterway would have to be a suspension span, in all likelihood, to obtain a safe horizontal clearance for that heavily travelled channel, the character of its vessel traffic, and adverse weather conditions. The main span over the Cape May Channel could be of a cantilevered truss or cable-stayed girder design."

In the aforementioned 1983 book, Crossing the Delaware: The Story of the Delaware Memorial Bridge, the author also mentioned that official reports were prepared for the DRBA in 1963 and 1970. Miller's description of the 1963 study is quoted below (pages 64-65). The studies specifically discuss a proposed bridge between Woodland Beach, Delaware and Sea Breeze, New Jersey.

"This report was distributed during the Authority's second meeting in March, 1963. It contained the findings of consulting engineers studying the feasibility of a new crossing between Cumberland County, New Jersey and Kent County, Delaware in the vicinity of Sea Breeze, New Jersey and Smyrna, Delaware. The study had been requested by the New Jersey Department of Transportation, with costs split between New Jersey and the Delaware Interstate Highway Division.

"The report concluded that a bridge in this area was not economically feasible at the time or in the foreseeable future. At 1963 prices, engineers estimated the project would cost $114 million for a four-lane and $64 million for a two-lane span.

Reluctant to deal with the possibility of a second southerly bridge, though local politicians from central Delaware and New Jersey (both areas which would have greatly benefited from such a decision) pushed for it, the Authority agreed to postpone further investigation of this proposed bridge. Instead, they chose to devote their time and efforts to the construction of a parallel span for the existing bridge and to the initiating of a ferry service between Cape May and Lewes."

Note that, when adjusting for inflation, these costs were estimated for the Delaware Bay Bridge. Inflation adjustments are based on comparing November of the proposal year and 2024.

| Year | Route | Width | Original Estimate | Inflation Adjusted Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | Woodland Beach to Sea Breeze | 2 Lanes | $64 million | $656 million |

| 1963 | Woodland Beach to Sea Breeze | 4 Lanes | $114 million | $1.17 billion |

| 1970 | Woodland Beach to Sea Breeze | 4 Lanes | $200 to $250 million | $1.59 to $1.99 billion |

| 1980 | Lewes to Cape May | 2 Lanes | $520 million | $1.92 billion |

| 1980 | Lewes to Cape May | 4 Lanes | $650 million | $2.40 billion |

The 1963 study was referenced in Crossing the Delaware (1983). The 1970 study was referenced in a 2021 editorial in the Cape May County Herald. The 1980 study is the one described in the previous section. In comparison, the South Jersey Transportation Authority estimated the long "on-hold" completion of New Jersey Route 55, a major freeway originally planned to link Philadelphia to Cape May and Wildwood, at over $1 billion in 2021. That would be for 20 miles of four-lane freeway.

Regardless, economic conditions in the 1970s, particularly due to the oil crisis, impacted any serious plans for a Delaware Bay Bridge. Miller's description is quoted below (page 65).

"The report stated that a suspension bridge could be built at this location, but that because of limited approach roads, the financial feasibility of the crossing could not be assured. An updated version of the report in 1970 stated that possibly by 1985 the feasibility could be expected to improve. The subsequent gas crisis activities since that time have in all probability delayed any serious consideration for this century."

While the original reports have proven elusive, I think I found their citations in a November 1972 study, Design Strategy in a Coastal Environment: Potential Improvements in Civil Engineering Design Techniques for Coastal Zone Planning (page 97). These citations are quoted below:

(17) "Engineering Studies on Location, Design, Cost, Traffic, Revenue, Feasibility, of the Proposed Delaware Bay Bridge," report by Howard, Needles, Tammen and Bergendoff, Consulting Engineers, New York, New York to the Delaware River and Bay Authority, and New Jersey State Highway Department, December 1962.

(18) "Report on Traffic Study for Proposed New Bridge Across the Delaware River Between Cumberland County, New Jersey and Kent County, Delaware," November 5, 1969, Coverdale and Colpitts, Consulting Engineers, 140 Broadway, New York, New York.

Alas, Miller cited the ultimate motivations for the parallel second bridge, instead of a more southerly location. These ultimately came down to the cost of constructing new approach roads, especially in the very marshy land on both sides of the Delaware Bay, and the funding mechanisms enabled by the then-new Interstate Highway system (emphasis added, page 72).

"There was considerable discussion as to where the second bridge should be built. The idea of a parallel span was not automatically decided upon. In fact, the thought of another crossing downstream seemed to have its merits.

One factor which stopped commissioners from deciding upon a more southern crossing was that officials from both states were apprehensive about the costs of constructing additional approach roads which would have been necessary for another bridge farther south. Another persuading argument for a parallel bridge was that in the late 1950's, Congress announced that federal funds would be available to pay 90 percent of the costs for a National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. The Memorial Bridge was included as a link in that system. Though the bridge itself would not be eligible for funding, approaches to the new crossing in each state would be. This would mean a substantial savings to both states.

New Jersey also agreed to interchange the Delaware Memorial Bridge approaches with the New Jersey Turnpike, Route 130, and a soon-to-be-built southern section of Interstate Route 295 on the New Jersey side of the river. All of these factors pointed toward a parallel bridge construction."

A summary of all these proposals is shown on the interactive map below. Tracings of maps were done by georeferencing in QGIS. Green represents the 1968 NJDOT Master Plan, red is the 1972 US-113 EIS, and orange is the 1980 DRBA study.

Within the 21st century, discussions regarding the feasibility of a Delaware Bay Bridge have continued. There has been some advocacy on both the Delaware and New Jersey sides of the river over the years.

There have been at least two bills that have been discussed within the Delaware General Assembly, one in 2003 and one in 2012. These primarily focused on a bridge-tunnel to replace the existing Cape May-Lewes Ferry. Both bills had Senator George Bunting, of Bethany Beach, as a sponsor.

The synopsis of the 2003 bill is quoted below (emphasis added). The synopsis of the 2012 bill is similar, but not as verbose.

"As it is currently operated, the Cape May-Lewes Ferry is neither an effective commuter conveyance nor a strong draw for tourists to Sussex County, losing millions of dollars each year. Other states have investigated alternatives to a ferry system and in some cases have constructed bridge/tunnel crossings to supplement or replace such a system. In addition to offering savings and convenience to the citizens of Delaware and New Jersey, the construction of a Delaware Bay Bridge/Tunnel Crossing would be an inspiring engineering feat and, when completed, could be used as a multi-purpose structure, acting both as a major route for interstate transportation and travel and a platform for wind turbines or tidal generation facilities to generate electricity desperately needed throughout Sussex County. This Joint Resolution directs the DRBA to conduct a study on the feasibility of constructing a Combined Bridge/Tunnel Crossing to traverse the Delaware Bay. This Joint Resolution also directs the DRBA to submit a report describing its research and findings to the Governor and the General Assembly no later than January 15, 2005."

Some local newspapers have advocated for the construction of a Delaware Bay crossing, also focusing on it replacing the Cape May-Lewes Ferry. A February 2021 editorial from the Cape May County Herald states:

"There was a moment in time when this county stood ready to be the crossroads for a traffic network. On April 15, 1964 the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel was opened creating a coastal transportation route north from the southern states. In July the ribbon was cut on the new Atlantic City Expressway linking Philadelphia with the still relatively new Garden State Parkway. A southern turn at Pleasantville would lead drivers down into Cape May County.

What stood between these two engineering accomplishments was the Delaware Bay, beginning in Cape May Point and ending in Lewes, Delaware. The answer in that same year was the Cape May Lewes Ferry, opened July 1, 1964. The ferry service got its start after the newly-established Delaware Bay River Authority [sic] (DRBA) purchased 4 ferries no longer needed in Virginia after completion of the Chesapeake bridge tunnel.

At the time, a bridge over the southern expanse of the Delaware Bay was contemplated but never financed. A 1969 engineering design firm study estimated that a 4 lane bridge would cost between $200 million and $250 million. The study came with a suggestion that a two lane bridge could save up to $100 million with the deferral of a second span until a future date."

Within the United States, there are several long crossings of large bodies of water. The list below is just a sample of those across the country, excluding those through swamps, bayous, and other shallow bodies of water.

| Approximate Location | Water Body | Bridge | Length | Opened |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annapolis, MD | Chesapeake Bay | Chesapeake Bay Bridge | 4.0 miles | 1952/1973 |

| Saint Petersburg, FL | Tampa Bay | Sunshine Skyway Bridge | 4.1 miles | 1987* |

| Newport News, VA | James River | James River Bridge | 4.4 miles | 1982** |

| Saint Ignace, MI | Straits of Mackinac | Mackinac Bridge | 5.0 miles | 1957 |

| Nags Head, NC | Croatan Sound | Virginia Dare Memorial Bridge | 5.2 miles | 2002 |

| Richmond, CA | San Francisco Bay | Richmond-San Rafael Bridge | 5.5 miles | 1956 |

| San Mateo, CA | San Francisco Bay | San Mateo-Hayward Bridge | 7.0 miles | 1967/2002 |

| Virginia Beach, VA | Chesapeake Bay | Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel | 17.6 miles | 1964/1999 |

* Replaces bridge dating to 1954. ** Replaces bridge dating to 1928.

For a Delaware Bay Bridge, a few locations were considered, of varying lengths.

| Year | Western Landing | Eastern Landing | Approximate Length* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Woodland Beach, DE | Sea Breeze, NJ | 5.1 miles |

| 1972 | Leipsic, DE | Sea Breeze, NJ | 6.2 miles |

| 1980 | Little Creek, DE | Beadons Point, NJ | 11.9 miles |

| 1980 | Lewes, DE | West Cape May, NJ | 16.0 miles |

* Approximate length over the Delaware Bay itself. Does not include any approach roads.

Naturally, the most commonly referenced reason for building a Delaware Bay Bridge is that Virginia built the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel (CBBT). While this does indicate that it is possible to build such a facility, it does not indicate the practicality of building such a structure.

Bridges are expensive. Tunnels are even more expensive. Virginia is currently expanding the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel (HRBT), which carries Interstate 64 and US Route 60 from Hampton to Norfolk, with two new bridges and tunnels. This will expand that facility from 4 lanes to 8 lanes. This cost estimate on this project is $3.9 billion.

Bear in mind that the HRBT is in a densely populated area, connecting to the largest Naval station in the world (Naval Station Norfolk) and the northernmost frost-free port in the eastern United States to the Interstate highway system. Additionally, the approach road (I-64/US-60) is already existing. The current shortfall of the HRBT is its lack of capacity. I've read in several forums that if someone lives in the Hampton Roads region, they need to live and work on the same side of the harbor, to avoid the constant congestion faced on the HRBT. Here, the economic benefits of the construction costs are clear.

The HRBT is just 3.5 miles long. The cities immediately served by the HRBT (Newport News, Hampton, Norfolk, and Portsmouth) have a combined population of just over 1 million. The Hampton Roads metropolitan statistical area, as a whole, has a population of 1.8 million.

On the other hand, the proposals for a Delaware Bay Bridge/Bridge-Tunnel range from 5 to 16 miles, suggesting higher construction costs. The counties immediately served by a Delaware Bay Bridge/Bridge-Tunnel (Cape May, Cumberland, and Salem in NJ; Kent and Sussex in DE) have a combined population of 765,000. Adding Maryland's Wicomico and Worcester Counties brings that population to just 925,000, about half the population of Hampton Roads.

Now, regarding the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, that represents an oddity. There's a substantial imbalance of population on both sides. The southern end is in Virginia Beach, the largest city in Virginia (though it was formed by consolidation from a suburban county, so it feels more like a large suburb of Norfolk). The northern end is on Virginia's Eastern Shore, a 70-mile narrow strip of land with a population of about 45,000. So why build such a facility? There are a few arguments to be made:

On the other hand, the Delaware Bay Bridge/Bridge-Tunnel simply cannot offer these types of benefits, at least not to the same degree.

Thus, I still feel there is not enough economic, travel, or practical justification for the expense and impacts involved in the construction of a Delaware Bay Bridge. While the thoughts of such studies are certainly interesting, there is simply not enough reason to construct such a large facility, especially when there are existing unmet travel demands.

One example of a wiser use of these funds is finishing the NJ-55 freeway, which suddenly terminates at NJ-47 about 20 miles north of Cape May and Wildwood, leaving NJ-47 a snarled mess on summer weekends. The South Jersey Transportation Planning Organization estimated that the cost of completing that highway would be over $1 billion. Estimates from the Delaware Bay Bridge/Bridge-Tunnel studies suggest that it would cost somewhere between $1.6 billion and $2.4 billion, when adjusting for inflation, while likely not relieving as much traffic as completing NJ-55.

Links were active at the publication of this article on December 26, 2024.