An exit from the Capital Beltway (express lanes) for Interstate 66, indicating tolls during morning rush hours. Footage from my dashcam.

Ask anybody who knows the Washington, DC region and I'm certain they'll tell you how awful the traffic is. Traffic in the area of the nation's capital has gotten so bad that Interstate 66, approaching Washington from its western suburbs in Virginia, implemented congestion-based tolls during rush hours starting in 2017, and sometimes these tolls are steep.

The Baltimore region, while being distinct from the Washington, DC region, is still close by, with the city centers only 40 miles apart. Both cities' beltways are only 20 miles from one another via I-95. Had Washington's outer beltway been constructed as planned, the Washington and Baltimore outer beltways would be just 12 miles apart via I-95.

Additionally, the two cities share a major airport, Baltimore-Washington International (BWI), and both are about 30 miles from Annapolis, the capital of Maryland. Among the major cities in the northeast megalopolis, Washington and Baltimore are a unique case, with the two arguably within commuting distance of one another.

As these two major cities are so close to one another, they can form a long stretch of congestion. Following I-95 from its first junction with the Capital Beltway to its last junction with the Baltimore Beltway involves a 71 mile trip, and both cities have more distant suburbs, especially Washington. Expanding the region further, from the Rappahannock River (Fredericksburg, VA) to the Susquehanna River (Perryville, MD), the trip on I-95 is 130 miles.

Traffic problems in these cities were recognized as early as the 1930s and Maryland had a solution, though it was going to be expensive. This is because Maryland contains some very large waterways, notably the Choptank, Patapsco, Patuxent, Potomac, Severn, and Susquehanna Rivers and, of course, the Chesapeake Bay. The state planned to build some major bridges in the 1930s, listed below.

| Waterway | Opened | Miles | From | To |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potomac River* | 1940 | 1.70 | Dahlgren, King George Co., VA | Newburg, Charles Co., MD |

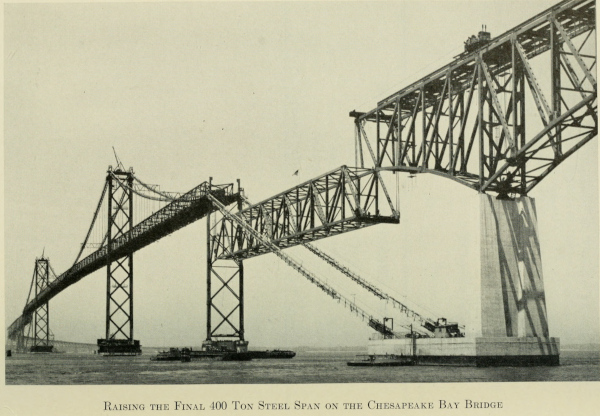

| Chesapeake Bay | 1952 1973** |

4.35 | Sandy Point, Anne Arundel Co. Originally Rocky Point, Baltimore Co. |

Kent Island, Queen Annes Co. Originally Tolchester, Kent Co. |

| Patapsco River*** | 1957 | 1.64 | Fairfield, Baltimore City | Seagirt, Baltimore City |

| Susquehanna River | 1939 | 1.44 | Havre de Grace, Harford Co. | Perryville, Cecil Co. |

* Replaced in 2022, original bridge demolished in 2023.

** Two lane eastbound span opened in 1952. Three lane westbound span opened in 1973.

*** Built as a tunnel.

The intent of this program is described in a 1938 study, Report on Estimated Traffic, Gross Revenue, and Toll Schedules for Susquehanna and Potomac River Bridges (page 16):

"In accordance with this authority the State of Maryland is seeking to develop a system of modern highway routes through the state which will serve the following purposes, to which the two bridges considered in this report will contribute:

(a) Relieve the increasing traffic on the single principal existing highway route between Baltimore, Maryland, and Richmond, Virginia.

(b) Provide routes by which the city congestion in Baltimore and Washington can be avoided by such traffic as does not need to pass through these cities.

(c) Link up the eastern and western shores of Maryland by an adequate vehicular crossing.

(d) Provide a settled nucleus of main highway routes from which further planning of state highways may be confidently developed."

The first two bridges in the table, the Potomac River Bridge (now called the Nice-Middleton Bridge) and the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, are the subject of this article. These were the bridges that were planned to offer an alternate route for long-distance travelers from Richmond and the south to the Delaware Memorial Bridge and the north, allowing these travelers to bypass the congested Baltimore/Washington area.

The Potomac River Bridge, later named for Governor Harry W. Nice and Senator Thomas "Mac" Middleton, is the southernmost crossing of the Potomac River and its only crossing south of Washington. It sits 30 miles due south of the I-95/I-495 Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge, the next crossing of the river.

The opening of the story of this bridge is described in the 1958 A History of Road Building in Maryland (page 145-146):

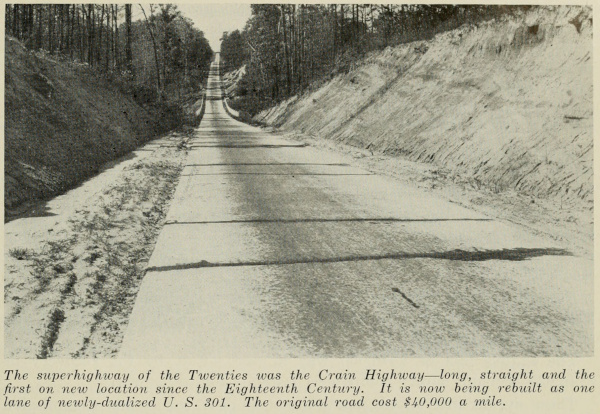

"After the Crain Highway was built in the Twenties to connect Baltimore with Charles County a southern extension across the Potomac into Virginia seemed inevitable.

Motorists southbound on U.S. 1, who had just studied in considerable detail the white-step architecture of Baltimore, complained that it took up to an hour to get through metropolitan Washington.

So Crain Highway, now U.S. 301, was extended to the river, Virginia built a connecting road and a beautiful new two-mile toll bridge was built by Maryland across the broad expanse of water which divides North from South."

The original bridge opened in 1940 and could be described as a project of wishful thinking at the time, despite Maryland's completion of the Crain Highway by the late 1920s, connecting Baltimore and Southern Maryland.

Some concerns remained about the southernmost stretches of the Crain Highway, between La Plata and Morgantown, as described in the 1938 study for the bridge (page 18):

"From La Plata south to Morgantown, the type is a fairly wide two-lane highway but without hard shoulders. This part of the highway would not be suitable for through traffic in its present condition and considerable expenditures would have to be made to put it in condition necessary to divert traffic moving on U.S. 1 south of Washington."

However, the Virginia side had no direct connection to the bridge and certainly no direct connection to the south (Richmond and beyond), as stated in the same study (pages 19-20, emphasis added):

"There is at present no direct highway connection from the proposed Virginia bridgehead near Dahlgren to the south. Traffic from Dahlgren moving to the south must now use Va. 206 running west to a junction with Va. 3 west of King George, then travel east on Va. 3 to Shiloh and then south on Va. 207 over the James Madison Memorial toll bridge (25-cent passenger car toll) across the Rappahannock River between Port Conway and Port Royal, and on to a junction with Va. 2 at Bowling Green.

[...]

It will be imperative to have a direct highway connection from the bridgehead to Shiloh or Port Conway if this bridge is to offer any inducement to through traffic or to local traffic. Present Virginia Highway 207 between Shiloh and Bowling Green is a good hard surfaced two-lane macadam highway except for the section on each side of the James Madison Memorial Bridge, which is narrow and unattractive. From Bowling Green to Carmel Church, on U.S. 1, the highway is narrow and curving with several small one-lane bridges. To make this section attractive to through traffic, and especially for trucks, a good deal of relocation and reconstruction will be required."

Ultimately, this study suggests that the main purpose of the Potomac River Bridge was to serve as a bypass of Washington for traffic from Richmond to Baltimore. While it wouldn't bypass Baltimore, it at least would remove one major hurdle for long-distance travelers. This is likely because there are no significant population centers near the bridge, so it wouldn't induce that much local traffic.

Newburg, Maryland is still 35 miles from Fredericksburg, Virginia and 75 miles from Richmond. Likewise, Dahlgren, Virginia is still 50 miles from Washington and 80 miles from Baltimore. While these may have improved travel times to these cities from the rural areas surrounding the bridge, clearly its construction was justified by offering a bypass of a major city, aiding long-distance travelers and separating them from traffic local to the Washington region.

Many sources noted that the construction of the Potomac River Bridge had a significant impact on traffic in both Maryland and Virginia. A 1950 study from the Maryland State Planning Commission, Probable Economic Effects of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge on the Eastern Shore, describes the impacts of the Potomac River Bridge (pages 30 and 35, emphasis added):

"Since the opening of the Potomac River Bridge near Morgantown in 1940, southbound traffic has increasingly followed U.S. 301 out of Baltimore across the Bridge directly to Richmond. This route has permitted traffic to by-pass Washington, D.C., completely and has accomplished a time saving of some 30 minutes.

[...]

Vehicles desirous of avoiding Washington on the way to Richmond and the South have used the Potomac River Bridge in large numbers. In the 12-month period ending September 1949, it was used by almost 900,000 vehicles. Only about 35 per cent of these were of Maryland origin. The others, with the possible exception of those of Virginia origin, were probably on long-distance trips."

A 1956 document, Highway Traffic Estimation, stated that travel agencies suggested long-distance travelers follow US-301 in their journeys (page 188):

"US 301 through Maryland and Virginia has been growing rapidly in traffic volume in the last few years, and this abnormal growth has been ascribed in part to the practice of routing agencies in suggesting the use of US 301. From 1950 to 1953 inclusive, the use of US 1 by out-of-state cars increased by 40 percent at Ashland, Virginia, whereas the use of US 301 by out-of-state cars increased 110 percent at Hanover, just east of Ashland."

The 1958 A History of Road Building in Maryland also described the large amount of traffic using the Potomac River Bridge (page 145-146):

"This $5,400,00 structure replaced no old bridge, as was the case at Havre de Grace. It was new construction on a new location and gave the public an entirely new route to the South.

[...]

The traffic engineers estimated the bridge would have 136,000 vehicles per year for the first five years. In 1942 the bridge carried 171,600 motor vehicles, in 1950, 1,008,000 and 1956, 1,958,000. The toll was set at 75 cents per passenger car at first, but has since been raised to $1.00."

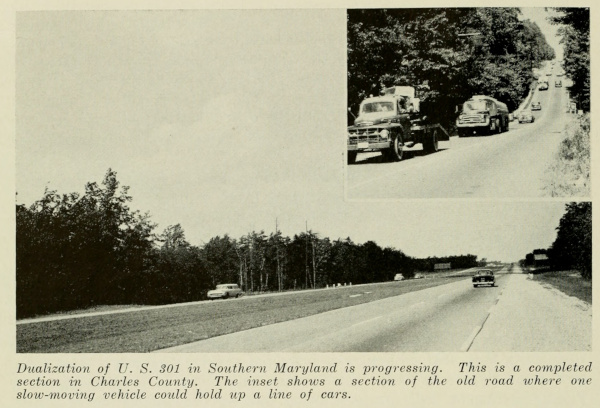

Given the claimed importance of the Potomac River Bridge and the timing of its construction, freeway routes were proposed to Southern Maryland, though they weren't built as planned. Improvements to existing arterial routes were built instead.

The Maryland State Planning Commission made the first mention of such a freeway route in the 1938 document Five Years of State Planning (page 19):

"It is interesting to observe that this last suggestion embodied the features that have recently been before the public as part of the State Roads Commission's Bridge Program. It is proposed a by-pass and bridge over Baltimore Harbor, a freeway by-passing Washington (but with ingress to both cities) to connect with a Potomac River bridge, the latter soon to be built with Federal funds."

In the 1950 document, Regional Aspects of the Comprehensive Plan, produced by the National Capital Park and Planning Commission, another reference to the freeway was made (page 34, emphasis added):

"(7) The Southern Freeway (Indian Head Highway).—Another route that was constructed during the last war, this highway will provide an all-purpose connecting highway between U.S. Route 301 and the District of Columbia. Route 301 is destined to become the most direct approach from the southern seaboard to the new Chesapeake Bay Bridge. It now provides the only bridge crossing of the Potomac River below Washington. An expressway connection to this bridge is thus of great future importance."

Other documents suggesting an eventual freeway connection to Southern Maryland include:

However, note that many of these documents recommend that the freeway connect the Potomac River Bridge to the Washington region, not necessarily to US-50 and eventually Baltimore.

The Maryland Department of Transportation also recommended some significant upgrades to the US-301 corridor in southern Maryland in 1976. The table below shows these proposals, listed from south to north.

| Priority | Area | From | To | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Critical | La Plata | Potomac River Bridge Toll Plaza |

Demarr Road | 6-lane divided highway |

| Critical | Waldorf | Demarr Road | 0.4 miles north of Acton Lane |

6-lane freeway |

| Critical | Waldorf | Smallwood Drive | N/A | Interchange |

| Critical | Waldorf | 0.4 miles north of Acton Lane |

Charles / Prince George's County Line |

6-lane divided highway |

| Non-Critical | Brandywine | Charles / Prince George's County Line |

Washington Outer Beltway* |

6-lane divided highway |

* The Washington Outer Beltway is beyond the scope of this article, but likely would have met US-301 near Rosaryville State Park.

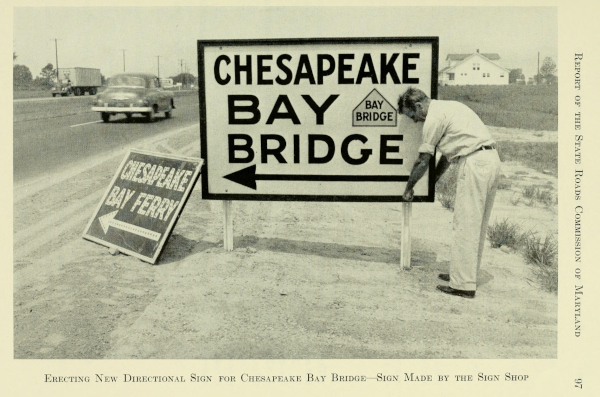

The most famous bridge in Maryland, if not the most famous bridge in the Mid-Atlantic, is the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. The two bridges form a beautiful 4.35-mile crossing of the Chesapeake Bay east of Annapolis. This section explores some the motivations for constructing this bridge.

Maryland's geography features a major gap, formed by the Chesapeake Bay. This effectively created two different worlds within the state. The immediate Western Shore of the Chesapeake Bay features Baltimore, Annapolis, and the Washington region, all major population centers within the northeast corridor. Meanwhile, the Eastern Shore, which is part of the Delmarva Peninsula, has always been very rural, with very little development.

To illustrate this difference, Salisbury, the largest city on Maryland's Eastern Shore, has a population of just 33,000. Meanwhile, Baltimore has a population of 585,000, and it peaked just shy of 950,000 in 1950. Dover, Delaware, the largest city on the Delmarva Peninsula, is only slightly larger than Salisbury, with a population of 39,400.

As the Eastern Shore has historically been isolated from the rest of Maryland, especially Baltimore, much of the trade from the Eastern Shore would be processed through the more readily accessible ports in Wilmington and Philadelphia. This suggested that the Eastern Shore felt more of a connection to Delaware and Pennsylvania, instead of Maryland.

Seeking to literally bridge the gap between the Western Shore and the Eastern Shore, consideration of a fixed crossing over the Chesapeake Bay dates back to at least 1926. Maryland's 1935 Ten-Year Highway Construction Program describes the potential implications for unified trade (pages 32-33, emphasis added):

"5. Eastern Shore Highway

The close link between Baltimore City and the various Eastern Shore communities, which was formerly provided by direct water transportation between these points, no longer exists. At present, the most accessible trading centers for the Eastern Shore using the existing highway facilities are Wilmington and Philadelphia. The provision of an adequate route to Baltimore by way of the suggested Chesapeake Bay Bridge, or a high speed ferry, should do much to reunite with mutually beneficial results the opposite sides of the Chesapeake Bay."

The earliest discussions of the bridge recommended a more northerly crossing, between North Point in Dundalk, just outside of Baltimore, and Tolchester, near Chestertown. Later discussions pushed it further south towards the current route from Sandy Point, near Annapolis, to Kent Island. This is discussed in further detail in the next section.

Note: I should start this section by mentioning that I've lived in Dover, Delaware for more than seven years. It is common knowledge on Delmarva that travelers should avoid the Bay Bridge on summer weekends. While I've never personally experienced hours-long delays, I've sat in traffic waiting to get on the bridge for at least 30-45 minutes on several occasions during busy weekends. This is a particular issue for Kent Island residents, as vacationers try to "jump the line" by using local roads approaching the bridge on Kent Island, leading MDOT to start shutting down ramps to the bridge during busy weekends to avoid this issue.

Arguably the most well-known destination for Bay Bridge travelers is the beaches. While Delmarva features far more than that, they are the main attraction for many tourists from Baltimore, Washington, and points west. Two separate statements made in 1936 Senate hearings discussing the eventual location of the Bay Bridge showed this emphasis:

A possibly cynical interpretation of this testimony could be that Washington politicians were in charge of these discussions, so these appeals were made to suggest that the politicians would have a much harder time reaching beach vacation destinations if the bridge were built at Baltimore instead of Annapolis.

Maryland's 1948 request to the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), which assigns Interstate and US Routes, for extending US-50 over the Bay Bridge also confirms this theory (pages 4-5, emphasis added):

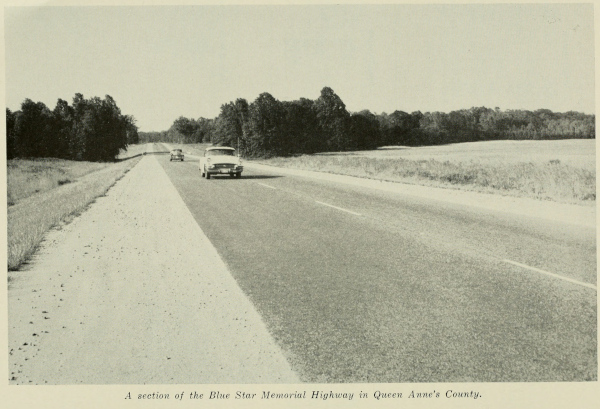

"Our reason for requesting this extension is that the present route as described above is carrying an appreciable amount of traffic with from 11 to 22 percent of vehicles bearing license plates other than Maryland. A number of improvements are scheduled in the near future along this route and many have already been completed. Some of the improvements contemplated are [...] a divided highway from the eastern approach to the bridge to Queenstown and Wye Mills. When these improvements are completed, together with those already accomplished, the proposed extension of U.S. Route #50 will carry one of the highest percentages of foreign traffic of any U.S. numbered highway in Maryland.

The proposed extension would provide a complete transcontinental route from the Atlantic Ocean in Maryland to the Pacific Ocean in California.

There is a recognized need for a U.S. numbered route running east and west between the head of the Chesapeake Bay and Cape Charles, Virginia. This proposed route would provide more adequate access from the interior to the Del-Mar-Va Peninsula, both for coastal defense and the motoring public in general."

It is also important to note that this request seemingly originated from the Berlin Lions Club. Berlin is 10 miles from Ocean City, suggesting local interest in promoting tourism to that area. At the time, US-213 connected Wye Mills (about 15 miles east of the Bay Bridge) to Ocean City. Today, US-50 overlays this section of the former US-213. The remainder of US-213, from Wye Mills to Elkton, is Maryland Route 213 today.

While improved access for vacationers may have been a large motivation for building the Bay Bridge, especially at its ultimate location, that only would serve seasonal needs. For such a large and expensive project, there needed to be a year-round use for it. And while the bridge would unify Maryland, there likely wouldn't have been enough traffic to and from the rural Delmarva Peninsula to justify the bridge.

However, in conjunction with the Potomac River Bridge in Southern Maryland, the Bay Bridge could serve another purpose. It could be the next link in the bypass of Baltimore and Washington, now offering a bypass of Baltimore. Earlier in this article, the intentions of Maryland's Primary Bridge Program were described, and one of the primary motivations was to use both the Potomac River Bridge and the Chesapeake Bay Bridge as this long-distance bypass for travelers from Richmond to Wilmington.

Numerous documents and studies on the Bay Bridge and highways connecting to it suggested this role. Maryland's 1950 Probable Economic Effects study, referenced earlier in this article, further suggests that the Bay Bridge would offer a major alternate route (page 34, emphasis added):

"Upon construction of the entire network of highways, of which the Bay Bridge will be an important link, motorists will have a through route over which they may move at high speeds, by-passing every major city en route.

[...]

These figures indicate that large numbers of motorist have recognized the advantages and have availed themselves of the existing facilities in order to avoid congested urban centers. To be sure, these facilities have increased the cost of the trip, but have at the same time effected a considerable saving of time. By using the Bay Bridge motorists will be able to accomplish a further time saving. It is estimated that at least one hour can be cut off travel time between the juncture of routes U.S. 13 and U.S. 40 in Delaware and routes U.S. 1 and U.S. 301 at Richmond, Virginia.

Certainly many motorists will be attracted to the new route for these reasons. The only major deterrent to its use may be the increased expense involved. [...] Experience has shown that usually the advantages of such a route have more than offset the increased expense."

Another document is Connecting Highways Between the Delaware Memorial Bridge and the Maryland Line Near Warwick, a 1950 study done for the Delaware State Highway Department. It outlined the advantages of the expressway system proposed in that document, which would provide a high-speed connection between the Delaware Memorial Bridge near Wilmington and the Chesapeake Bay Bridge (page 10, emphasis added):

"The Knappen Tippetts Abbett Engineering Co. made test runs on existing alternate routes to obtain values of time, distance and delay via the existing routes for comparison with estimated values for routes via the New Jersey Turnpike and high type connecting highways in Delaware and Maryland. From a common point opposite Camden, New Jersey, to Washington, D.C., the expressway system would be slightly longer than the shortest alternate route via Baltimore. However, it was estimated on the basis of the test runs, with consideration of average conditions of congestion on the alternate existing routes, that the expressway system would effect time savings of three-quarters of an hour to an hour and a quarter and would reduce the number of stops required from the present total of 35 or more to approximately three."

Interestingly, this same study warned of capacity limitations on the single Chesapeake Bay Bridge and that even when just considering potential increases in through traffic on the Bay Bridge (i.e., without an origin or destination on the Delmarva Peninsula), it would be outgrown relatively quickly (pages 10 and 12):

"However, on this basis, the capacity of the bridge can be taken at about 11,000 vehicles per day. [...] The average daily bridge traffic having origins or destinations within the Delmarva Peninsula south of Warwick is estimated at approximately 4,000 vehicles for 1955. The remaining capacity, available for through traffic, would accommodate approximately 7,000 vehicles per day in that year.

[...]

A large part of the traffic between the Delaware Memorial Bridge and Washington, D.C. and points south and west would use the proposed expressway systems in Delaware and Maryland if not limited by roadway capacities. However, even with conservative estimates of diversion, generations and growth, the estimated demand would soon exceed the anticipated capacity available for through traffic on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. As explained above, that available capacity is estimated at about 7,000 vehicles per day in 1955 and no further increase could be expected. Other volumes on a connecting highway in Delaware would include traffic between Wilmington and points north and east, and the areas adjacent to the proposed Maryland Expressway, estimated at about 3,300 vehicles per day by 1970. These volumes, together with local traffic, would create a demand on a connecting highway in Delaware in excess of 14,000 vehicles per day by 1970."

Note that the original Chesapeake Bay Bridge span, which opened in 1952, has two lanes. The bridge was supplemented with a second span in 1973, which features three lanes.

Numerous documents from the 1950s and early 1960s describe the impact of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge on long distance traffic. However, it must be noted that the once promised US-301 freeway in Delaware, which would connect the controlled-access US-301 expressway in Maryland with I-95 a few miles west of the Delaware Memorial Bridge, was not built until the late 2010s, almost 70 years after the Bay Bridge opened.

Traffic Quarterly, from Quarter 2 of 1953, suggested that the Potomac River Bridge saw significantly increased traffic after the opening of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. However, it appeared that most of the traffic actually using the Bay Bridge had a destination on the Delmarva Peninsula (page 175 and 178, emphasis added):

"From data available, it appears that traffic on the Susquehanna River Toll Bridge has continued at approximately the normal rate of increase, while traffic on the Potomac River Bridge has increased about three or four times the normal rate of growth.

[...]

The crossings of the Chesapeake Bay during August, 1952, the first full month of operation of the bridge, were 146,000 more than the number of vehicles carried by the ferry system during the preceding month. The tremendous increase appears to be mostly induced traffic as evidenced by the lack of any significant diversion from US Route 40 and US Route 13, the two routes on which any diversion would be noticeable.

During July, 1952, the last month of operation of the ferry system, an origin and destination survey was conducted; a similar survey was conducted during August, 1952 on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. Preliminary indications are that a large percentage of the increase of 146,000 vehicles using the bridge compared to the ferry, was composed of trips between the Baltimore and Washington areas and the Delmarva Peninsula."

I would imagine that a major confounding factor in this origin and destination survey is that it was conducted during the summer, which is obviously peak beach season. Additionally, some major road improvements had yet to be made at the time, particularly the "Eastern Shore Expressway," today's US-301 connecting the Bay Bridge to Delaware, which may have hindered traffic looking to follow the alternate route.

The Maryland State Roads Commission's 1958 A History of Road Building in Maryland specifically said that the bridge "furnished a short-cut for north-south traffic, an effective bypass of Baltimore and Washington traffic" (page 148). It stated that traffic increased from 1,919,000 vehicles in 1953 to 2,836,000 in 1957, a 48% increase. Even at this time, only one carriageway of the Eastern Shore Expressway was open.

In 1959, Maryland filed a request with AASHTO to completely reroute US-301 from Bowie (US-50). Originally, US-301 followed today's MD-3 to Baltimore. Maryland's 1959 request moved US-301 to multiplex with US-50 through Annapolis and over the Bay Bridge, then split at Queenstown. At this point, US-50 would continue south and east to Ocean City, by way of Easton, Cambridge, and Salisbury. US-301 would continue northeast towards Middletown, Delaware and eventually Wilmington. In fact, part of Maryland's apparent primary motivation was to simplify routes for long-distance travelers (page 20, emphasis added):

"1—U.S. Route 301 is one of the heaviest traveled north-south routes and at present terminates in the north-south corridor in Baltimore City. For simplification of long trip travel it should be extended to the junction of U.S. 13 and U.S. 40 in Delaware where direct connection is made to the New Jersey Turnpike via the Delaware Memorial Bridge.

2—While the distance between the junction of U.S. 301 and U.S. 50 and the junction of U.S. 40 and U.S. 13 in Delaware is slightly longer via the proposed route, it is shorter in travel time.

3—There are only 16 miles of the 88 miles between the junction of U.S. 50 and U.S. 301 to the junction of U.S. 40 and U.S. 13 in Delaware, via Baltimore City and U.S. 40, that has any type of access control. All of the proposed routing in Maryland (75.4 miles) is either limited or controlled access."

Apparently the rerouting of US-301 was successful in creating this long-distance bypass route, as described in the 1963 Wilbur, Smith, and Associates study, Highway Travel in the Washington-New York-Boston Megalopolis (page 67, emphasis added):

"Chesapeake Bay Bridge—Capacity limitations on U.S. Route 40 in Maryland and the difficulties formerly encountered in the congested city traffic of Baltimore have caused many motorists to bypass this section by following U.S. Route 301 from northern Delaware to Annapolis, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. Since the Chesapeake Bay Bridge was opened to traffic in July, 1952, traffic on this route has virtually doubled, increasing from 5,300 in 1953 to 10,500 in 1962. The compound rate of increase on this route since the bridge replaced the ferry has been 7.9 per cent per year. In the nine years since the Bay Bridge has supplemented the Susquehanna River Bridge in accommodating travel in this corridor, growth on the Susquehanna Bridge has averaged only 1.9 per cent per year; and, in combination, the growth on the two bridges has been 3.3 per cent per year."

This section covers two recent and significant upgrades to the US-301 corridor, specifically the US-301 freeway in Delaware and the new Potomac River Bridge.

Outside of US-50/301 between Bowie and Queenstown, much of the US-301 corridor had not been built as a full freeway. In Delaware, it took several decades to build the long promised US-301 freeway.

In January 2019, Delaware finally opened the proposed US-301 freeway as a toll road. My article on the Delaware Route 1 freeway describes some of the history of the proposals for that highway, which date back to at least 1950. However, the proposals for a US-301 freeway, through 1993, suggested that the Summit Bridge would be used to cross the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal. The current Summit Bridge was constructed with freeway-like approaches for that reason.

Instead, the US-301 freeway was built south of the canal and traffic to that highway uses DE-1 and the Roth Bridge. There are plans for a spur route from Delaware's US-301 freeway to directly reach the Summit Bridge.

In October 2022, Maryland opened a replacement crossing of the Potomac River. While the old crossing was a beautiful continuous truss bridge, it was very narrow, with two traffic lanes and no shoulders. The new bridge features four lanes, though without shoulders, meaning that the whole bypass route now has at least four lanes.

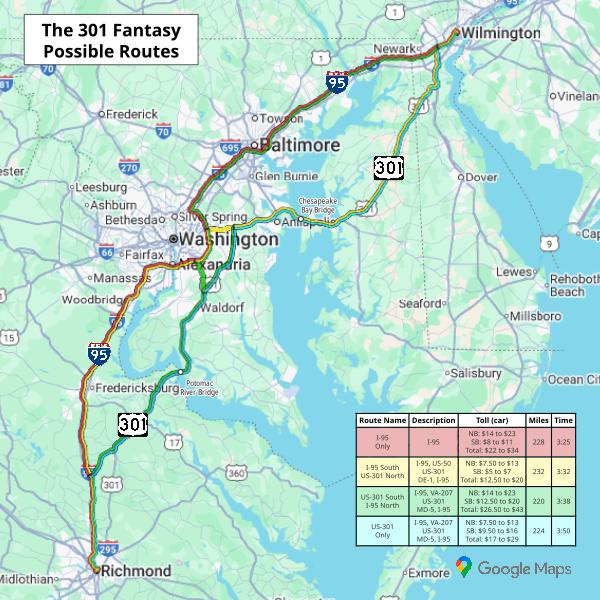

Note: The travel times for each of these routes assume ideal traffic conditions.

| Route Name | Route Description | Toll (car) | Miles | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-95 Only | I-95 | NB: $14 to $23 SB: $8 to $11 Total: $22 to $34 |

228 | 3:25 |

| I-95 South US-301 North |

I-95, US-50 US-301 DE-1, I-95 |

NB: $7.50 to $13 SB: $5 to $7 Total: $12.50 to $20 |

232 | 3:32 |

| US-301 South I-95 North |

I-95, VA-207 US-301 MD-5, I-95 |

NB: $14 to $23 SB: $12.50 to $20 Total: $26.50 to $43 |

220 | 3:38 |

| US-301 Only | I-95, VA-207 US-301 DE-1, I-95 |

NB: $7.50 to $13 SB: $9.50 to $16 Total: $17 to $29 |

224 | 3:50 |

Source: Google Maps, Delaware Department of Transportation, Maryland Department of Transportation

Links were active at the publication of this article on September 2, 2025.